Our final profile in the “Pioneers of Yokohama” series honors the earliest of Yokohama’s pioneers—a man so hyperactive and indefatigable, with contributions in so many fields, that he is justly called “The Father of Yokohama.” Takashima Kaemon (1832-1914) was born in Ginza, the heart of Edo (old Tokyo), as the sixth son of a lumber merchant. He took over his father’s business at the age of fourteen and five years later assumed the crippling debt revealed by his father’s sudden death. Taking advantage of the destruction caused by the Ansei Earthquake and Fire of 1854 and the ensuing need for timber to rebuild, this enterprising young man made his first fortune rebuilding the lavish mansions of the feudal lords of Saga and Morioka. A crisis can be an opportunity for an ambitious young man!

With the opening of international trade in 1859, Takashima seized the chance to make another fortune in the port city of Yokohama. Using his Saga connections, he sold high-quality porcelain from the kilns of Imari to his new Western customers. However, he fell afoul of currency control regulations and was sent to prison for six years. On his release in 1865, the unabashed entrepreneur promptly resumed his headlong pursuit of new opportunities, running a construction firm which built the British consulate and opening Yokohama’s first hotel, Takashimaya (no connection to the department store), with a mixture of Western and Japanese styles. This led to an alliance with the British ambassador as well as lifelong friendship with the government officials who enjoyed his hotel’s hospitality—among them future prime ministers Itō Hirobumi and Ōkuma Shigenobu.

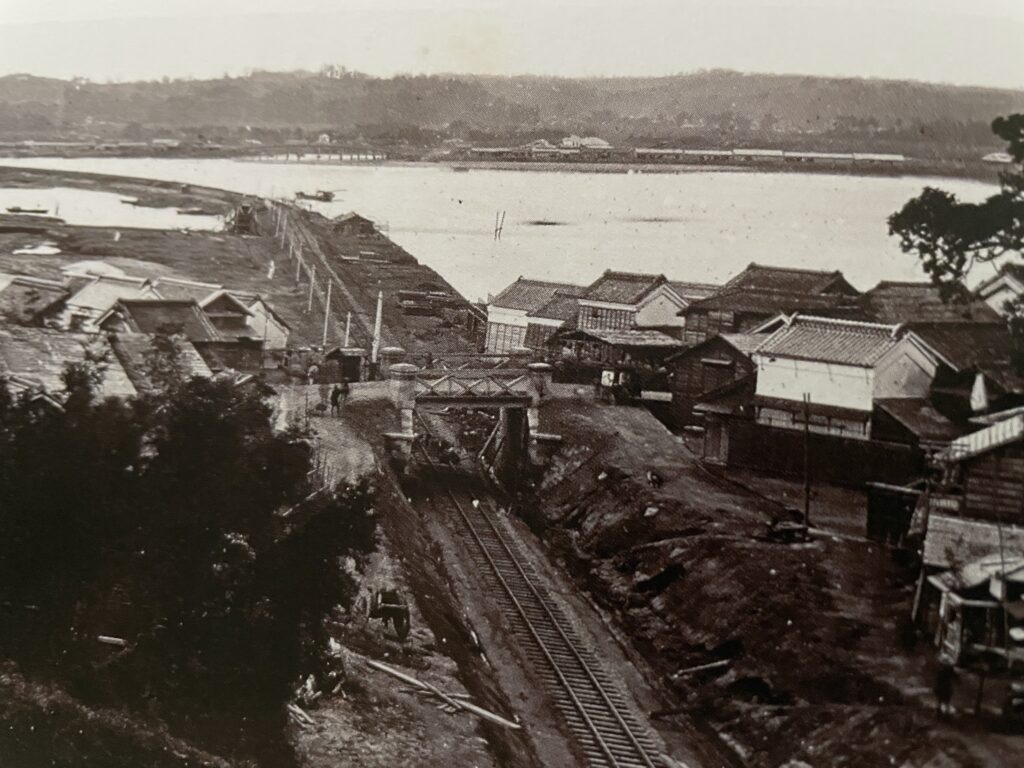

Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, one of the new government’s top priorities was the construction of a railway between Shimbashi in Tokyo and the station in Yokohama now called Sakuragi-chō. The route required a causeway across open water and the Hiranuma Lagoon, where Yokohama Station stands today on land reclaimed from Tokyo Bay. Slicing a wide path through a considerable hill north of the station also added to the difficulty. Ōkuma hired Takashima, who in turn hired 3000 workers, and they completed the job in just 140 days, in time to lay the track for the opening of Japan’s first railway in 1872. Today eight rail lines thread through the canyon he heroically excavated.

In later life, Takashima was instrumental in building railways in Hokkaidō and elsewhere in Japan. However, it was his contribution to Yokohama’s rails that led to seven different train stations bearing his name at one point, three of which remain today: two underground stops on the Minato-mirai and Blue Lines as well as a JR Freight cargo depot.

Takashima’s boundless dynamism led him in that same busy year to introduce gas lighting to Yokohama, a first for Japan and two years earlier than the capital. The Yokohama Gas Company office stood on the current site of Honchō Elementary School in Hanasaki-chō, where you’ll find a gas light and plaque to memorialize it. (You might recognize the company by its current name, Tokyo Gas.) When he installed gas lights in the Imperial Palace, Takashima may have been the first commoner whom Emperor Meiji ever met. His company brought coal from Hokkaidō in his own fleet of ships, and he pioneered what later became the Tokyo streetcar network. Meanwhile, he turned his attention to education, donating his own money to found one of Yokohama’s first schools, in partnership with educator Fukuzawa Yukichi.

At the peak of his success in 1876, Takashima abruptly retired to his vast estate on the hill now called Takashima-dai, looking down on Takashima-chō below. In the annual ranking of wealth on a sumō-style banzuke (a document listing the sumō rankings), he was one of only five Yokozuna (the highest rank), and the only one outside of Tokyo. Even thirty years later, his occupation was listed simply as “Millionaire,” as he was otherwise uncategorizable.

Takashima’s career epitomized the potential for Meiji-era “rags to riches” ascent through once impermeable social class barriers. His restless energy propelled him to build the infrastructure of Yokohama, transforming a raw, raucous port into a modern city.