Let’s begin with a short questionnaire: Have you ever walked from Bashamichi to Isezaki-chō across Yoshida-bashi Bridge? Ambled along the broad sidewalks of Nihon-Ōdōri Boulevard, shaded by bright yellow ginkgo trees in autumn? And then sauntered into Yokohama Park to view the tulips in springtime? Wandered over to Ōsanbashi Pier to gaze out at the ships in Yokohama harbor? Have you ordered a product online from overseas, hoping that the ship carrying it would safely enter that harbor? Have you turned on the faucet, confident that clean water would emerge? More prosaically, flushed your toilet recently? (Please do so.)

If your answer is “Yes” to any of the above, spare a moment to thank two prolific British civil engineers, Richard Henry Brunton (1841-1901) and Henry Spencer Palmer (1838-1893). Brunton arrived in Yokohama from Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1868, the year of the Meiji Restoration, as a foreign advisor to the new government. In the next eight years, he transformed a rough-and-ready frontier outpost with muddy streets, raw sewage, and frequent fires, into a clean and modern port city. During Palmer’s eight years in Yokohama, from 1885 to 1893, he developed Yokohama harbor and its piers, planning and building Japan’s first waterworks system to provide potable water to residents of the fast-growing city. No need to buy bottled water—just turn on your tap!

Brunton was hired to design and build lighthouses, and 26 of them rose above the Pacific coast under his supervision, an average of one every three months. From Hokkaidō to Kagoshima, in all weather and inaccessible locations, Brunton and his team worked continuously, inventing new methodology to fit the Japanese terrain. Amazingly, all but four of them are still in operation. (That’s why your package from Amazon arrived at your doorstep.) Fellow Aberdonian Iain Maloney spent years climbing them all, as documented in his recent book, The Japan Lights.

Palmer was born into a British Army family stationed in Bangalore (now Bengaluru) in southern India and followed tradition by entering the Royal Corps of Engineers in 1856. Following his first five-year overseas assignment in Vancouver, Canada, he worked as a surveyor and astronomer in New Zealand, Barbados, and Hong Kong, before arriving in Yokohama in 1885 as a civil engineer for the Japanese government. The burgeoning population of the port city needed fresh water, and Palmer led a complex operation to deliver it—all the way from Yamanashi! You can still visit his waterworks headquarters in Hodogaya-ku. He built the original Ōsanbashi Pier, most recently reconstructed in 2002 with an award-winning design resembling a whale. Palmer’s distinctive lion-head taps graced many public areas, including the plaza outside Sakuragi-chō Station. (See the exhibit inside the station building.)

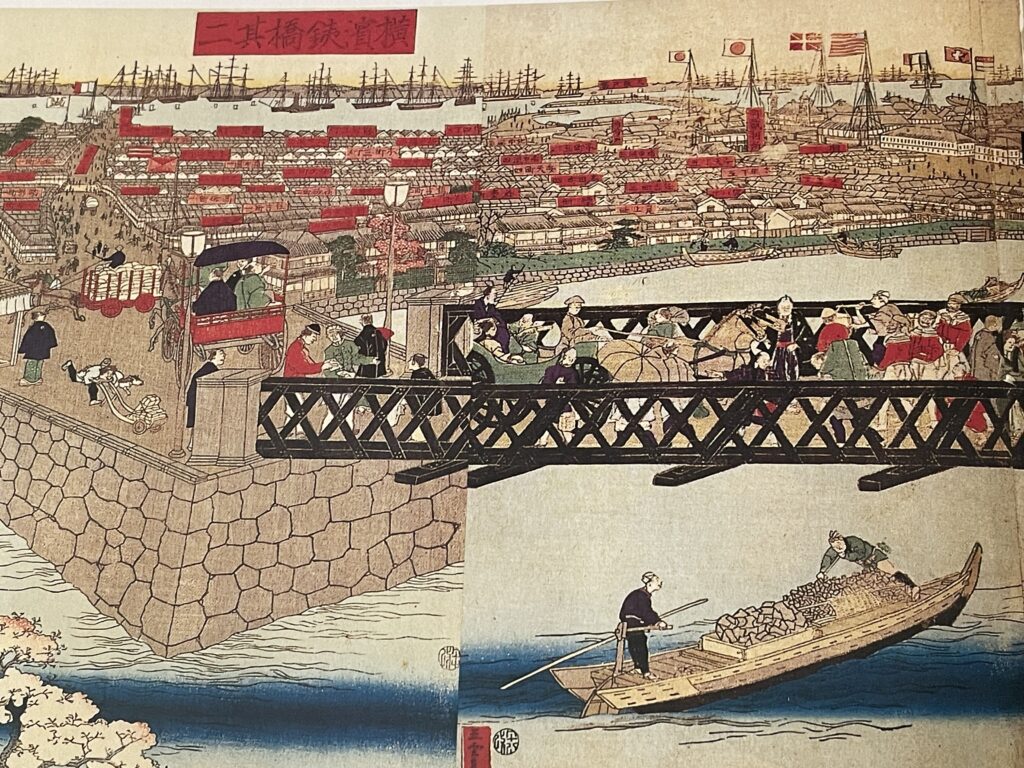

Ambitious, practical, hard headed, and brusque, Brunton typified the Scotsmen who laid the foundations for the British Empire. Not content with his original assignment, he took it upon himself to rebuild Yokohama after a devastating fire. Streets were paved, drainage improved, a telegraph system established, and the first iron bridge constructed in Japan linked Bashamichi with Isezaki-chō. Brunton designed Nihon-Ōdōri, a broad avenue with sweeping vistas, as a firebreak to prevent future conflagrations from spreading. An exhibit nearby displays his egg-shaped brick sewer pipes, which vastly improved the aroma of the town. Yokohama Park, now centered around its baseball stadium, provided a relaxing green space for foreign and Japanese residents alike. A statue of Brunton greets visitors to the park at its eastern gate.

Palmer’s personality was more placid than Brunton’s, but his ambitions were no narrower. Using Yokohama as his model, he designed the waterworks in Kōbe, Hakodate, Tōkyō, and Ōsaka. He prospered in Japan, a country that he loved. After retirement from the Royal Engineers as a Major-General, he married and lived in Tōkyō until his death at age 54 of typhoid fever. His statue in Nogeyama Park honors his contributions to Yokohama.

By contrast, Brunton was by all accounts an irascible and disagreeable character, picking fights with his employers and colleagues. One such conflict led to his termination and return to Britain in 1876. Yet his lighthouses have saved countless lives over the decades since. Lift a glass to this grumpy protean polymath—and where else but at Bruntons, his namesake craft beer bar in Chinatown?